2022-09-01

A value strategy posits that the worth of an asset tends to oscillate around a more gradual, underlying trend. When an asset’s current value falls below this trend, it is deemed undervalued and becomes an attractive acquisition. Conversely, we considered it overvalued when it exceeds the trend, presenting an opportunity for short selling. In this exploration, we develop a simple model designed to estimate and elucidate the expected performance of such a strategy. This model encapsulates the essence of the quantitative value approach and provides practical insights into the dynamics of asset valuation and investment decision-making in today’s financial markets.

At the core of this model lies the concept of log prices and fair values. Define p_t=\log{P_t} as the log price of an asset at time t and v_t=\log{V_t} the log fair value of the asset at time t. The valuation process is key to understanding this model, denoted as X_t = p_t - v_t. This process represents the difference between the market price and the fair value in logarithmic terms. When X_t>0, it indicates that the market price P_t is above the fair value price V_t by a factor of e^{X_t}, i.e. by (e^{X_t}-1)\times 100\% in percentage terms (and for small gaps, this is approximately X_t\times 100\%). Conversely, X_t<0 indicates that the market price P_t is below the fair value. A value X_t=0 signifies that the asset trades at its fair value.

The dynamics of X_t follow an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process, a well-established method for representing mean-reverting behaviour. In this process, X_t reverts towards zero, representing the fair value in our context, with a certain speed of mean reversion \theta and a volatility \sigma. The initial condition is X_0 = 0, which implies that the asset starts at its fair value. Mathematically, this process is described by the stochastic differential equation:

dX_t = -\theta X_t dt + \sigma dW_t \tag{1}

This equation captures the essence of mean reversion: -\theta X_t dt pulls the value back towards the mean, while \sigma dW_t adds a random fluctuation, reflecting the inherent asset return volatility.

To analyze this process further, we utilize a few useful identities. First, we can express X_t as normally distributed with a mean of zero and a time-dependent variance.

X_t \sim N\left(0, \frac{\sigma^2}{2\theta}\left(1-e^{-2\theta t}\right)\right) \tag{2}

This distribution reflects how the variance of X_t evolves.

Lastly, for analytical convenience, we introduce s_t^2, a scaling factor for the variance of X_t. By defining

s_t^2 = \frac{\sigma^2}{2\theta}\left(1-e^{-2\theta t}\right),

we can standardize X_t such that

\frac{X_t}{s_t} \sim N(0, 1) \tag{3}

This standardization simplifies further analysis, allowing us to work with a standard normal distribution and facilitating a more straightforward interpretation and application of statistical methods.

In this section, we delve into the implications of assuming a constant fair value for the asset in this model. This assumption simplifies our understanding of the valuation process, X_t, and its relationship to the asset’s log price, p_t.

By considering the fair value, v_t, as a constant, we essentially equate the change in X_t with the instantaneous log return of the asset, dp_t. This equivalence leads to an important insight: the log return of the asset, under this assumption, follows a mean-reverting process devoid of any drift component. It is a crucial simplification that allows us to focus on the mean-reverting nature of the asset’s price without the additional complexity of a drifting trend.

The strategy is continuously rebalanced and aims to exploit this mean reversion. The strategy operates by trading in opposition to the current valuation; specifically, it sells when the asset is overpriced (i.e., when X_t>0). The instantaneous profit and loss \pi_t at time t can be expressed as:

dY_t = -X_t\,dp_t = -X_t\,dX_t

We then examine the cumulative PnL process

Y_t = \int_{0}^{t} -X_u\, dX_u \tag{4}

with initial condition Y_0=0. Integrating this expression yields:

Y_t = -\frac{X_t^2 - \langle X_t \rangle}{2} = \frac{\sigma^2 t - X_t^2}{2}

Equation Equation 3 implies that X_t^2 \sim s_t^2 \chi_1^2 where \chi_1^2 is a Chi-squared distribution with 1 degree of freedom. Moreover, \mathbb{E}(X_t^2)=s_t^2, leading us to the distribution of Y_t

Y_t \sim \frac{1}{2}\left(\sigma^2t - s_t^2 \chi_1^2\right) \tag{5}

with its expected value being \mathbb{E}(Y_t)=\left(\sigma^2 t - s_t^2\right)/2.

We now focus on a risk-adjusted performance metric for the mean-reversion strategy. In continuous time, there are multiple reasonable notions of “risk.” The terminal (end-point) variance of the annualized PnL can shrink with horizon even when the path experiences substantial fluctuations. To reflect the volatility of the path—which is what matters for drawdowns and margin—we measure risk using the quadratic variation of the PnL process.

The first moment, or the expected value of the annualized PnL over a time horizon t, is derived as follows:

\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}\left[\frac{Y_t}{t}\right] &=\frac{1}{t}\,\mathbb{E}\left[\int_0^t -X_u\, dX_u\right] \\ &=\frac{1}{t}\,\mathbb{E}(Y_t) \\ &= \frac{1}{2}\left(\sigma^2 - \frac{s_t^2}{t}\right) \end{aligned} \tag{6}

To quantify the path risk, we compute the expected annualized quadratic variation of the PnL process. Starting from

dY_t = -X_t\,dX_t = \theta X_t^2\,dt - \sigma X_t\,dW_t,

the martingale component is -\sigma\int_0^t X_u\,dW_u, and therefore the quadratic variation of Y is

d\langle Y\rangle_t = \sigma^2 X_t^2\,dt.

Taking expectations and annualizing over the horizon t gives

\begin{aligned} \frac{1}{t}\,\mathbb{E}\left[\langle Y\rangle_t\right] &= \frac{1}{t}\,\mathbb{E}\left[\int_0^t \sigma^2 X_u^2\,du\right] \\ &= \frac{1}{t}\int_0^t \sigma^2\,\mathbb{E}(X_u^2)\,du \\ &= \frac{1}{t}\int_0^t \sigma^2 s_u^2\,du \\ &= \frac{1}{t}\,\frac{\sigma^4}{2\theta}\left(t + \frac{e^{-2\theta t}}{2\theta} - \frac{1}{2 \theta}\right) \\ &= \frac{\sigma^2}{2\theta}\left(\sigma^2 - \frac{s_t^2}{t}\right). \end{aligned} \tag{7}

We then define a continuous-time (path-based) Sharpe ratio at horizon t as the mean annualized PnL divided by the square-root of the annualized quadratic variation:

\mathrm{SR}_t := \frac{\mathbb{E}[Y_t/t]}{\sqrt{\mathbb{E}[\langle Y\rangle_t]/t}} = \sqrt{\frac{\theta\left(\sigma^2 - \frac{s_t^2}{t}\right)}{2\sigma^2}} \tag{8}

Taking t to infinity yields the asymptotic annualized Sharpe ratio.

\mathrm{SR} = \lim_{t\rightarrow \infty} \mathrm{SR}_t = \sqrt{\frac{\theta}{2}} \tag{9}

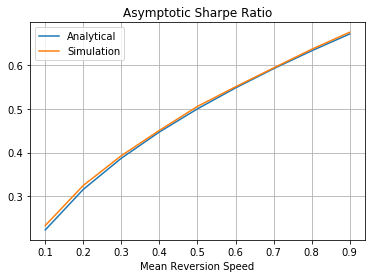

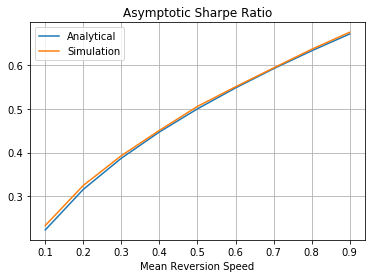

Figure 1 shows the asymptotic expected (path-based) Sharpe ratio as a function of the mean reversion speed \theta. We produce the simulation results (shown in orange) by generating 1000 PnL paths of the strategy with t=100 and \sigma=0.1. Each path is discretized into 252 trading days in a year. Different \sigma values are also tried and yield the same result.

The primary contributor to the expected annualized PnL is the term \sigma^2/2. This term originates from the quadratic variation \langle X_t \rangle, a critical component in our model that reflects the strategy’s profit from trading effectively in fluctuating markets–buying when prices are lower and selling when they are higher. This aspect of the strategy is a frictionless continuous-time effect tied to quadratic variation; in practice it is sensitive to discretization, trading costs, financing, and position limits.

However, the expected returns are offset by the variance of the valuation gap \mathbb{E}(X_t^2). This variance plays a dual role: it increases with the asset’s volatility and decreases as the speed of mean-reversion, \theta, increases. This relationship implies that when the volatility is high relative to the speed of mean reversion, the valuation gaps may persist for extended periods, thereby increasing the holding costs of our positions.

Similarly, the asymptotic Sharpe ratio, a measure of risk-adjusted return, is shown to be directly proportional to the mean reversion speed \theta while remaining unaffected by \sigma. Equation Equation 8 shows that \theta influences the path volatility of the strategy’s PnLs. Meanwhile, an increase in mean reversion speed leads to reduced volatility of average PnLs, subsequently enhancing the Sharpe ratio.

A few more extensions of the model reveal further complexities when we introduce variations. If the unconditional mean is estimated with a constant bias, an intriguing phenomenon emerges: the expected PnL remains stable, but there is a noticeable increase in its variance. This increase is directly influenced by the asset’s volatility and the magnitude of the bias, leading to a consequential decrease in the expected IR of the strategy. Moreover, the model indicates that when the unconditional mean is estimated without bias but possesses a positive (or negative) correlation with the log price, the expected PnL is impacted adversely (or favourably).

A particularly notable finding from our analysis is the impact of correlation on the trailing estimates of fair value. We demonstrate that a positive correlation can occur with any trailing estimate, presenting a nuanced insight into the behaviour between the fair value and the log price. This aspect of the model underscores the complexity inherent in mean-reversion strategies and highlights the critical importance of accurate parameter estimation in maximizing the efficacy of such investment approaches.